Implementing a CHIP-8 emulator

Writing a simple emulator from scratch is fun: rCHIP8

I’ve written about the CHIP-8 machine before. It is a very simple interpreted programming language that can be implemented without much hassle by anyone interested in getting their feet wet with emulators. It is commonly regarded as the “hello world” of emulators.

Some time ago I decided to implement a CHIP-8 emulator in Rust as my second project written in that language. My first foray into the language was the porting of the Gaia Sky LOD catalog generation tool from Java. This allowed us to substantially increase the generation speed and dramatically (really) decrease the memory consumption of the processing, to the point where a processing that previously needed more than 2 TB of RAM could now be done with less than a hundred gigs. Back to the topic at hand, I called my implementation rchip8 (very creative). This post describes the process and structure of such an emulator with more or less detail.

If you know nothing about CHIP-8 I would recommend you to at least skim-read the specification. This post will be more fun if you know a little about the machine itself.

I implemented the full emulator in two sessions of approximately one hour each. After the first session the basic structure and functionality (display, internal clock, registers, interpreter) was already there, but some of the instructions were still missing. In the second session I implementing these instructions, ironed out some of the bugs and added a few command line options to make it more flexible.

You can find the source repository for this implementation here.

Basic structure

My emulator is organized into 8 main modules:

- Main module:

main.rs - Machine:

chip8.rs - Display:

display.rs - Audio:

audio.rs - Keyboard input:

keyboard.rs - Time:

time.rs - Debug utils:

debug.rs

The main module

The main module controls and uses the rest. It implements the CLI argument parsing, initializes the machine with all its modules, and it also implements the main loop. The main loop contains the event loop, and the call to the machine cycle. The main loop also updates the display module if needed, and uses the Beep utility in the audio module to sound the beeper when needed.

The implementation accepts a few CLI arguments, which are parsed using clap. The arguments are well documented when running the program with -h.

R-CHIP-8 0.1.0

Toni Sagrsità Sellés <me@tonisagrista.com>

CHIP-8 emulator

USAGE:

rchip8 [FLAGS] [OPTIONS] <input>

FLAGS:

-d, --debug Run in debug mode. Pauses after each instruction, prints info to stdout

-h, --help Prints help information

-V, --version Prints version information

OPTIONS:

-b, --bgcol <bgcol> Background (off) color as a hex code, defaults to 101020

-c, --fgcol <fgcol> Foreground (on) color as a hex code, defaults to ABAECB

-i, --ips <ips> Emulation speed in instructions per second, defaults to 1000

-s, --scale <scale> Integer display scale factor, defaults to 10 (for 640x320 upscaled resolution)

ARGS:

<input> ROM file to load and run

The initialization happens immediately after the CLI arguments have been parsed, and goes over the main modules and creates the relevant structures: the SDL2 context, the Display manager, the Beep (audio), and the actual Chip8 machine:

| |

Once that’s done everything is ready to start the main loop. It is actually very, very simple:

| |

Even though the main loop is in the main module, the actual timing of the machine is controlled by the machine module. We’ll see that later. The machine also sets some flags that are used in the main loop to operate the display and audio modules. These flags are the following:

display_clear_flag– if up, the display must be cleareddisplay_update_flag– if up, the display must be updated using thechip8.displaybufferbeep_flag– if this flag is up, the machine must beep

The machine

This module contains the machine data structures, is in charge of initializing the registers, memory and counters, and also implements the interpreter that parses and executes instructions and times them correctly according to the instructions per second setting.

The Chip8 struct contains the data structures:

- RAM – a 4 kB (4096 bits) array of

u8, initialized to 0, implemented as[u8; 4096] - Registers – sixteen one-byte registers, implemented as

[u8; 16] - The index register

I– a 16-bit register used to store memory addresses, implemented asu16 - The stack – a LIFO array of 16-bit values used for subroutines, implemented as a

[u16; constants::STACK_SIZE] - The program counter

PC– the memory location of the current instruction, implemented as anusizeused to index the RAM - The delay and sound timers

DTandST– two 8-bit registers used for timing and sound, implemented as a couple ofu8fields - The display buffer – the buffer used to store the on/off state of each pixel in the display, implemented as a

[u8; constants::DISPLAY_LEN], whereDISPLAY_LENis 64*32=2048

The CHIP-8 machine does not really specify this, but it is common to use the first 80 bytes of RAM to store sprite fonts for the HEX characters from 0 to F. My implementation does this too:

| |

The ROMs (programs) to be executed are just a series of bytes that will be interpreted as instructions. Some ROMs also contain data or sprites. By default, the ROM should be copied to the machine RAM at the address 0x200. The program counter PC is, then, initialized to the same address, since that’s where the first program instruction resides.

| |

The cycle() method

The cycle() method in the Chip8 structure of chip8.rs is called in every iteration of the main loop. This method does a few things:

- Updates the delay timer

DTand the sound timeST. These timers must be decreased 60 times per second if their value is greater than 0. To do so, thecycle()method gets a time as argument (t: u128is the current time in nanoseconds), which is then compared against the last time that the method was called. If this value is over 16.666.666 (1/60 seconds in nanoseconds), then the timers are updated if needed. - Interprets the next instruction if the timing is right. The

Chip8has the instruction time in nanoseconds. This is the number of nanoseconds between instructions. So, if the current time minus the last time is greater than this value, the next instruction is interpreted. - Updates the last time record with the current time, in preparation for the next call to

cycle().

Each instruction is 2 bytes long (4 hexadecimal digits) and are stored with the most-significant byte first. Instructions have the one of the format CXYN, CXNN or CNNN, where each of the characters is 4 bits, or a hexadecimal digit. C is the code or group. X and Y are typically used to refer to register numbers. N, NN and NNN are 4, 8 and 12-bit literal numbers used to set values or for further instruction identification within a group (since 4 bits would only allow for 16 instructions). Instructions are decoded by splitting them into chunks and grouping them accordingly.

First, we need to get the instruction from the RAM address of PC, and increase the PC two words:

| |

Then we decode the current instruction into C, X, Y and N, NN and NNN. This is easy with some bit shifting:

| |

Finally, we need to match the instruction code and optionally N, and perform whatever actions defined by the instruction. Find a precise description of each CHIP-8 instruction in my previous CHIP-8 specification post. My implementation of these instructions is here.

In this post we discuss in detail only 0xDXYN, which is the draw instruction. Its definition is this:

0xDXYN: DRW VX, VY, N – draw the sprite at position VX, VY with N bytes of sprite data at the address stored in I. Set VF to 01 if any pixels are changed to unset, and 00 otherwise. 1

The interpreter must read N bytes from the I address in RAM. These N bytes are interpreted as a sprite and drawn at the display coordinates [VX, VY]. The bits are set using an XOR with the current state. This is my implementation of the instruction:

| |

Note that at the end we set the display flag to true so that the main module can update the display module with the modified display buffer. Let’s have a look at the display module next.

The display

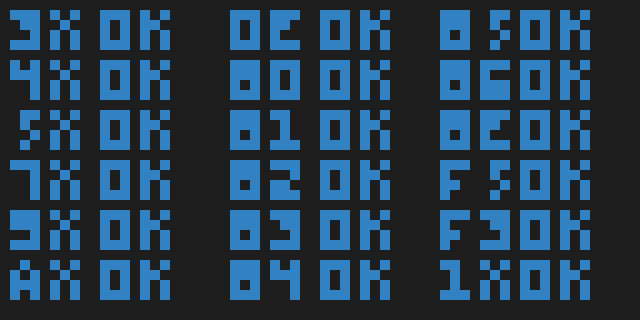

rCHIP8 display output with test ROM.

The display is in charge of drawing stuff. It is implemented with SDL2 using the sdl2 Rust bindings.

The base CHIP-8 display has only two colors (monochrome), and works with a resolution of 64x32 pixels. [0, 0] is at the top-left corner, while [63,31] is at the bottom-right.

[0,0] [63,0]

┌───────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ │

│ 64x32 DISPLAY │

│ │

│ │

└───────────────────────────────┘

[0,31] [63,31]

The graphics are drawn using 8x15 sprites, but this module knows nothing about this. Its only responsibilities are creating the window, drawing a buffer to the canvas, and clearing the canvas when requested. There are two main functions in this module:

clear()– clears the display to the configured background colordraw(buffer: [u8; DISPLAY_LEN])– which draws the contents of the given buffer to the canvas using the configured foreground color

Additionally, the display takes in as parameters the foreground color, the background color, and a scale factor. The scale factor is used to increase the size of the display. The default size is 640x320, which corresponds to a scale factor of 10.

pub struct Display {

pub canvas: Canvas<Window>,

pub event_pump: EventPump,

pub scale: u32,

pub fgcol: Color,

pub bgcol: Color,

}

Audio

This module is very simple. It contains a single struct called Beep, which connects to an audio device. The module emulates the beep produced by the system beeper. It contains the play() method, which starts the beeper, and the pause() method, which stops it. It is called in the main loop.

Keyboard

This module only contains a couple of functions to convert bytes into SDL2 scan codes and vice-versa. This is used to map the CHIP-8 input keypad to the left chunk of the QUERTY keyboard:

1234

QWER

ASDF

ZXCV

The map() method is simple, and contains a single match:

| |

The unmap() method is equally simple, this time in the opposite direction.

Time

Nothing to see here, really. This module only contains a single method to get the current system time in nanoseconds.

Debug

This module contains some debugging utilities that are used when rchip8 is started wit the -d or --debug flags. In that case, the execution is paused after each instruction and the contents of the main data structures (counters, registers, etc.) are printed out. This is a good mode to enable if you need to study how the internal state of the machine changes with each instruction.

Conclusion

In this post I have presented a Rust implementation of the CHIP-8 machine. We have seen each of the different modules and their responsibilities. There are many extensions and variations that could be added, like the CHIP-8X, the CHIP-8X or the S-CHIP (also called Super-Chip). These add different features like new instructions or additional display modes. I may implement some of them into rchip8 in the future.